White Spaces

White SpacesOn the 7th of this month I

tweeted about the FCC’s approval of a conditional unlicensed use of the

White Space television spectrum, asking followers what would they do with their own white space.

White spaces are unused parts of the TV airwave spectrum, usually kept that way to avoid transmission overlapping and interference. On 17th of February 2009, the US will stop broadcasting analog TV, becoming purely digital, which will free up even more electromagnetic frequencies.

White spaces have been referred to as “Wi-Fi on steroids” (not Asteroids, I know, Charlie), because it is possible to build a broadband connection that, contrary to wi-fi, has a more robust signal capable of crossing concrete walls and many of the obstacles that weaken wi-fi transmission.

Atari's Asteroids

Atari's AsteroidsPerhaps, Wi-Fi on “Asteroids” (a consequence of the mix of a momentary drunkenness and my Brazilian accent) refers to the unimaginable myriad of new options that White Spaces can bring to the networked society. At the moment, discussions and ideas spin around possibilities from bringing broadband to digitally unreachable rural areas to arranging the urban traffic system by collecting data from vehicles, meaning, your car slows down automatically when the one in front of you breaks. But this is less than a grain of sand in the desert compared to what’s about to come. This is big, and we still have no clue how huge this will be.

Here in this blog, I often mention the term

TV III, which refers mostly to the radical changes in the distribution link of the media industry value chain. Disintermediation is the buzz word that’s been a constant character in the nightmares of many CEOs of broadcasting networks. Many media conglomerates rushed to acquire digital bridges to desperately fill the gap in the broken value chain, some with more success than others. Some companies spent millions in digital companies with no clue whatsoever of what to do with them. Others, cleverly used their new digital endeavours to expand the reach of their televised content, adapting programmes to become new touch points to the company’s branded confinements. Fewer of them even managed to create a participatory viewer culture creating a legion of fans around branded communities. But those who are most likely to win the TV III race are not the broadcasters, but the digital companies who saw beyond reach and found the gates of the Platform Era.

International Business Machines

International Business MachinesIn an

older post I touched upon how I’ve been seeing the evolution of the computer industry and how, at its third stage, it blends completely with the media business.

First, there was

The Hardware Era, when the machine was the holy grail. Faster machines, make them smaller, the dream of a personal computer (who would care to use one of this things? In the kitchen? Anyone?). The Hardware Era land was reigned over by kings like IBM and HP. And then the “hippies” joined the party, with their dreams of mass computing and interface metaphors, and thus the second era began:

The Software Era. It doesn’t matter what machine it is, as long as gives me the tools I need. Bow to Bill Gates, Windows and Microsoft. And then the years progressed, the internet was born, a connected society started to rise, and all of a sudden, neither hardware, nor software really mattered anymore. Of course, we all heard about the “war of the browsers” that's still being fought, but whoever wins it it doesn’t matter much, as long as it works as a reliable gate to the platforms, the place where people can express themselves thorough user generated content and where companies can thrive their businesses. In the past we had an economic structure made of costumers, retailers and wholesalers. But in

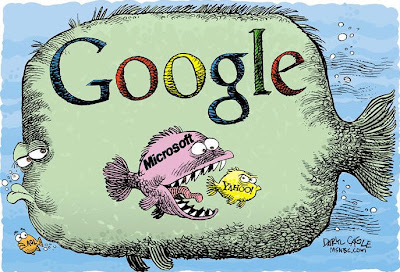

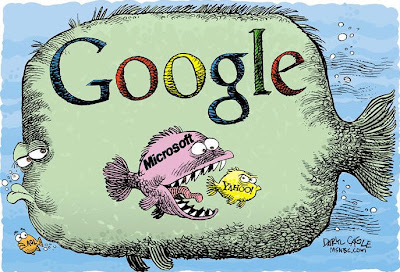

The Platform Era, platforms are the wholesale of the wholesalers. Platforms are the atmosphere where the whole digital business ecosystem breathes in. In the Platform Era, Google has been leading the way with successful experiments like Google Ad Words and YouTube.

There is always a bigger fish

There is always a bigger fishThe word disintermediation should be applied more carefully. Incumbent distribution gatekeepers have lost some of their power, but at the same time, a new category of intermediators has risen, and I say they are even more powerful then the old ones. I’m not anti-Google. I believe platforms are very effective artificial marketplaces. It is just that intermediation reached another level. Companies and individuals are now allowed to talk to the world and make business in ways never imagined. But frankly, this is not real freedom. It’s like that story of the fish that is unaware of the water. And on top of that, there is always a bigger fish.

So getting back to the White Spaces. The word is on the streets and it’s on the news: white spaces are destined for greater things. Things the internet failed to accomplished, such as the creation of a real uncontrolled environment, with no governmental or industrial ownership. Mobile phones that connect with each other directly without the use of operator companies, affordable broadband to everyone, the creation of free networks for education, and many other innovations to come.

Free competition, no control, disintermediation. A perfect scenario to implement a platform to bring all lose ends together. There is a reason why campaigns such as

Free the Airwaves are sponsored by Google, and I bet you won’t find Newscorp Inc., or any other giant media conglomerate on the list of companies behind the

Wireless Innovation Alliance, the coalition for companies behind the lobby for the unlocking of White Spaces.

Sponsored by the "don't do evil" Google

Sponsored by the "don't do evil" Google

Whilst broadcasters frown upon the idea of a new massive competition, Google prepares the soil to seed a whole new land of search ads on browsers, android and whatever innovative tools they’ll come up with to support and spread the Google ads system.

Even if the White Spaces generate millions of new TV channels in a very long tail, Google is the most prepared enterprise to herd audiences to their content. As a platform, at the end of the day, Google could easily become The Matrix.

Apart from that, White Spaces still have a long way to go in terms of engineering and even ethics. Take for example how hard is to track some pedophiliac websites, and how harder it may get in the uncontrolled White Spaces.

At least we know that ARGs will find new cool places to hide their puzzle crumbs. New branded touch points for everyone.

I've been absent for a while (visitors in town), and on top of that I've spent some time doing research about the appropriation of TV brands, which eventually became a collaborative post in a friend's blog while he was on holidays (sorry, only in Portuguese, but you can give google translate a try), but which will soon be translated/adapted and posted in this very blog.

I've been absent for a while (visitors in town), and on top of that I've spent some time doing research about the appropriation of TV brands, which eventually became a collaborative post in a friend's blog while he was on holidays (sorry, only in Portuguese, but you can give google translate a try), but which will soon be translated/adapted and posted in this very blog.

.jpg)

.gif)

.jpg)